Validating Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Dermatology: From Proof of Concept to Clinical Tool

A neural network achieved 8.95% mean error in psoriasis BSA estimation, compared to 27.84% for a board-certified dermatologist, establishing the foundation for AI-assisted skin assessment.

Introduction

This article describes peer-reviewed academic research that preceded and informs the development of Dermi Atlas. The algorithms and methods discussed are not currently available as features in any Dermi product. Dermi Atlas is a clinical photography and image management platform. The integration of research capabilities into the platform is a long-term development goal.

When researchers at the 1956 Dartmouth Conference coined the term "artificial intelligence," the idea of machines diagnosing skin disease would have seemed absurd. Yet here we are. Modern AI, built on neural networks whose interconnected nodes loosely mimic biological synapses, has proven remarkably adept at learning complex, nonlinear patterns in visual data. And few medical specialties are as visual as dermatology.

Dermatologists diagnose and monitor skin diseases largely by looking at them. That reliance on visual pattern recognition is both the specialty's strength and its vulnerability: how accurately a clinician assesses a rash depends heavily on their training, experience, and even how tired they are that day. Two dermatologists examining the same patient can arrive at meaningfully different severity estimates, and this inter-rater variability has real consequences for treatment decisions.

Nowhere is this problem more apparent than in Body Surface Area (BSA) estimation, the percentage of a patient's skin affected by disease. BSA underpins virtually every major severity index in dermatology: the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD), and Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI). The standard clinical approach, the "palm method," assumes that one patient palm equals roughly 1% of BSA. But planimetric studies have shown the actual figure is closer to 0.78%, a built-in error that cascades through every calculation that depends on it.

Various computer-based alternatives have been tried: automated total-body imaging (ATBI), Computer-measured Psoriatic Area (ComPA), and the optical pencil (OP) method, among others. Each moved the needle toward objectivity, but none struck the right balance of accuracy, cost, and clinical practicality to gain wide adoption.

It was in this context that Breslavets and colleagues posed a simple question: could an artificial neural network estimate psoriasis BSA more accurately than a trained dermatologist?

The Validation Study

The study design was deliberately straightforward. Breslavets et al. assembled 130 de-identified photographs of psoriasis from a community-based dermatology clinic, then asked four evaluators to estimate the affected skin percentage in each image: a board-certified dermatologist, two undergraduate science students with no specialized dermatology training, and a trained artificial neural network (ANN).

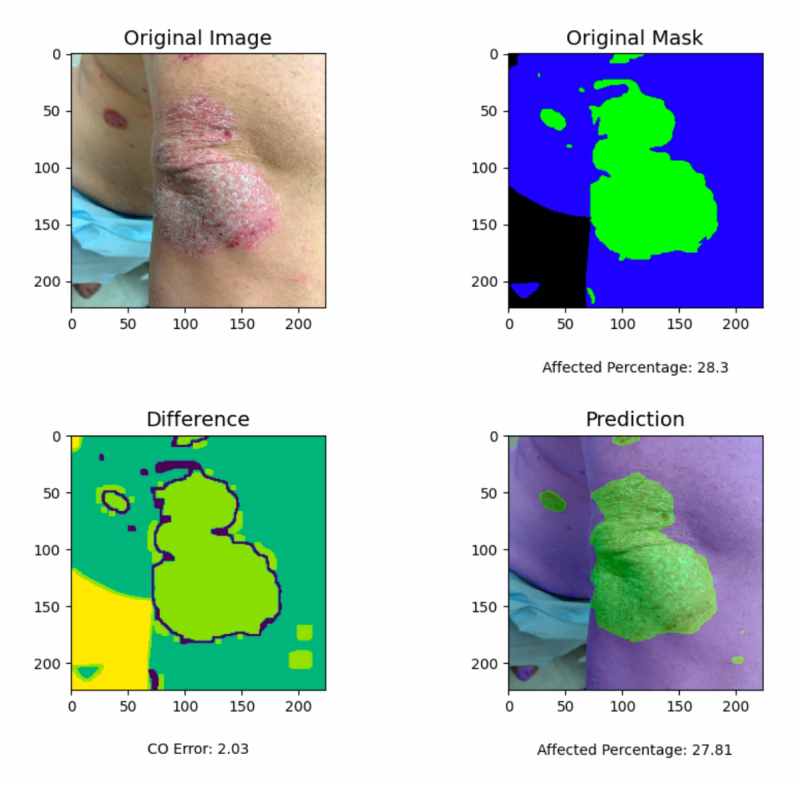

The ANN was a 17-layer convolutional neural network (CNN) built in Python with TensorFlow, accepting input images at 224×224 or 448×448 pixels. It had been trained on over 2,000 unaltered psoriasis photographs, each paired with a manually annotated mask outlining healthy versus affected skin. The network's job was conceptually simple: count the pixels classified as psoriasis, count the pixels classified as healthy skin, and compute the ratio. Despite this apparent simplicity, the task directly mirrors what clinicians attempt during physical examination, only with pixel-level granularity instead of gestalt estimation.

An important practical detail: the team deployed the tool both as a desktop application and as an Android mobile app. If AI assessment tools are going to matter clinically, they need to work where clinicians actually are: in exam rooms, at bedsides, on the go. Statistical comparisons used the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test, a non-parametric method well-suited to the likely skewed distribution of estimation errors.

Results

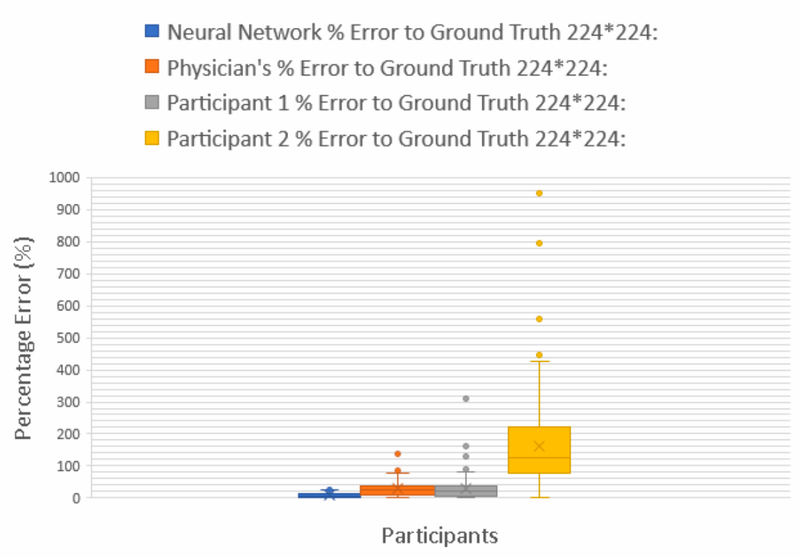

The numbers were unambiguous. The ANN achieved a mean percentage error (MPE) of 8.95% (SD 13.94%, 95% CI [6.55, 11.34]). The board-certified dermatologist came in at 27.84% (SD 15.89%, 95% CI [25.11, 30.57]), roughly three times the neural network's error. Participant 1, an undergraduate student, was close behind the dermatologist at 29.23% MPE. Participant 2 recorded an MPE of 162.1%, suggesting a fundamental misunderstanding of the task or a systematic calibration problem.

All pairwise comparisons between the ANN and human evaluators were statistically significant (p < 0.05). The mobile application produced identical results to the desktop version, confirming that the deployment platform did not compromise performance.

What stands out is not just that the ANN was better, but how much better. This was not a marginal improvement requiring large samples to detect; it was a clear, clinically meaningful gap. A machine learning model trained on a few thousand labeled images could consistently beat an experienced physician at a core clinical measurement task.

Broader Context

These results did not emerge in a vacuum. By 2022, AI had already made inroads across several areas of dermatology. Phillips et al. had shown AI could outperform human evaluators in melanoma detection from dermoscopic images. Esteva et al.'s influential 2017 study demonstrated a CNN classifying malignant versus benign skin lesions at 76.5% accuracy, with sensitivity of 96.3% and specificity of 89.5%, outperforming two dermatologists who achieved 65.6% and 66.0% respectively.

The smartphone app landscape told a more mixed story. Published evaluations of AI-powered dermatology apps reported sensitivity ranging from 7% to 73% and specificity from 37% to 94%, a spread so wide that it said more about the inconsistency of the field than about the technology itself.

On the adoption side, though, clinicians were broadly receptive. Surveys consistently showed that most dermatologists viewed AI favorably: 73.4% considered it useful for diagnosis and treatment planning in one study, 77.3% agreed it would improve diagnostic capabilities in another, and only 5.5% expressed worry about being replaced. Familiarity with AI correlated strongly with positive attitudes (P < 0.001), suggesting that as dermatologists learn more about these tools, resistance tends to decrease.

Meanwhile, on-device inference frameworks like TensorFlow Lite and Apple's CoreML were making it feasible to run neural networks directly on smartphones, keeping patient data local and sidestepping the privacy concerns that come with cloud-based processing.

Why This Study Mattered

The Breslavets validation study was significant for several reasons beyond its headline results.

First, even the experienced dermatologist could not match the algorithm. The undergraduate students' poor performance was expected, since they lacked training. But the dermatologist's threefold error disadvantage suggested the problem was not about training per se but about the inherent limits of human visual estimation for quantitative tasks.

Second, the mobile deployment mattered. A desktop application is useful for research; a phone app is useful for clinical practice. Showing equivalent performance on both platforms demonstrated that AI-assisted BSA estimation could be practically accessible, not just theoretically possible.

Third, the study targeted quantification rather than diagnosis. Much of the AI-in-dermatology literature had focused on classification (is this lesion malignant or benign?), which puts AI in direct competition with a dermatologist's core expertise. BSA estimation, by contrast, is a quantitative task that even experienced clinicians find tedious and imprecise. Framing AI as a measurement tool rather than a diagnostic rival made the work easier to accept and easier to integrate into existing workflows.

Limitations

The study had clear constraints. All 130 images came from a single clinic, so center-specific factors (camera equipment, lighting, photographic technique) could have influenced results. The patients represented Fitzpatrick skin types 1 through 4 only; how the algorithm would perform on darker skin tones remained an open question with significant equity implications. Difficult anatomical sites like the scalp and genital areas were not systematically assessed. The training set of 2,000 images, reasonable for 2021, would be considered modest by current deep learning standards. And comparing against a single dermatologist offered limited insight into the range of expert performance.

What Came Next

Despite these limitations, the study accomplished something important: it established that AI-based BSA estimation was not just feasible but practically superior to expert human assessment. The working mobile app made this more than an academic exercise.

The natural follow-up questions were obvious. Could the approach handle full-body assessment, not just individual photographs? Could it incorporate regional analysis across standard anatomical segments? Could it be validated against multiple dermatologists with a more rigorous ground truth?

These questions would drive the next phase of the research program: the development of the SPREAD (Skin Patch-based Regional Extent Assessment for Dermatoses) Framework and the subsequent AI PASS comparative study, both of which would build on the foundation laid by this initial validation work.

References

Breslavets, M., Shear, N. H., Lapa, T., Breslavets, D., & Breslavets, A. (2022). Validation of Artificial Intelligence Application in Clinical Dermatology. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 86(1), 201–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.064

Breslavets, M., Shear, N. H., Breslavets, D., & Lapa, T. (2023). Use of Artificial Intelligence as an Objective Assessment Tool in Clinical Dermatology. EADV Symposium, Seville, Spain.

Esteva, A., Kuprel, B., Novoa, R. A., Ko, J., Swetter, S. M., Blau, H. M., et al. (2017). Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature, 542, 115–118.

Phillips, M., Greenhalgh, J., Marsden, H., & Palamaras, I. (2020). Detection of Malignant Melanoma Using Artificial Intelligence: An Observational Study of Diagnostic Accuracy. Dermatology Practical & Conceptual, 10(1), e2020011.

Was this article helpful?

Your feedback helps us improve our content

Related Articles

Read more news

Stay up to date with our latest announcements