AI Versus Dermatologist: Findings from the AI PASS Comparative Study

The AI PASS study found that AI achieved a mean absolute error of 0.668 in BSA estimation, compared to dermatologist errors of 2.31 to 5.55, with statistical significance across all comparisons.

Introduction

This article describes peer-reviewed academic research that preceded and informs the development of Dermi Atlas. The algorithms and methods discussed are not currently available as features in any Dermi product. Dermi Atlas is a clinical photography and image management platform. The integration of research capabilities into the platform is a long-term development goal.

The earlier validation study (JAAD, 2022) showed that a neural network could estimate psoriasis BSA more accurately than a dermatologist, but it did so using a single-image approach, one dermatologist comparator, and a relatively simple ground truth methodology. Those results were promising, but they left open the question of whether a more sophisticated AI system, evaluated under more rigorous conditions, would hold up.

The AI PASS study (AI Versus Dermatologist Performance in Psoriasis Body Surface Area Assessment) was designed to answer that question. It deployed the full SPREAD Framework (described in the previous article in this series) against three independent dermatologists, using a consensus-derived ground truth rather than a single-rater reference standard. The results, published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, were decisive.

The core question was clinically consequential: BSA estimation directly influences decisions about systemic therapy, disease monitoring, and clinical trial endpoints. If AI can do this more accurately and consistently than trained specialists, that has practical implications for how we manage patients.

Study Design

The Image Cohort

The study analyzed 35 anonymized color photographs from a dermatology clinic archive, with approval from the Institutional Research Ethics Board. The images were selected to represent a range of psoriasis severities and distributions. Some showed widespread trunk involvement, others showed more localized disease on the extremities. Both front and back views were included. This heterogeneity was intentional; the evaluation needed to reflect the kinds of presentations clinicians actually encounter.

Thirty-five images is a smaller cohort than the original 130-image study, but the methodological rigor was substantially higher.

Establishing Ground Truth

Three dermatologists independently reviewed each photograph and provided two types of assessment: severity grading of erythema, induration, and desquamation (each on a 0–4 scale), and BSA estimation with anatomical segment annotation.

Their three independent assessments were then synthesized into a consensus ground truth. This is a stronger reference standard than single-rater annotation because it captures collective expert judgment while reducing the influence of any one assessor's idiosyncratic biases. It is not perfect (the dermatologists themselves showed variability), but it represents a meaningful improvement over prior approaches.

The AI System

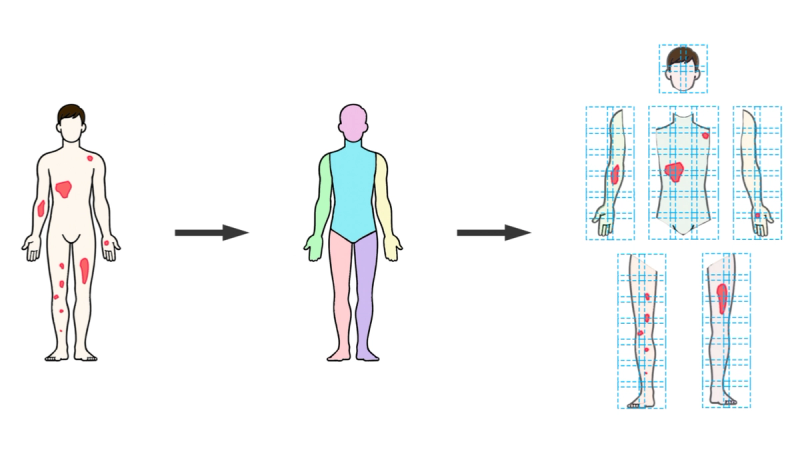

The AI system was the full SPREAD Framework pipeline: DensePose body segmentation, sliding window patch formation, UNet 3+ semantic segmentation classifying each pixel as background, healthy skin, or psoriasis, and metric aggregation across anatomical regions. The severity classification component (SWIN Transformer) was excluded to keep the evaluation focused on spread quantification.

Segmentation Performance

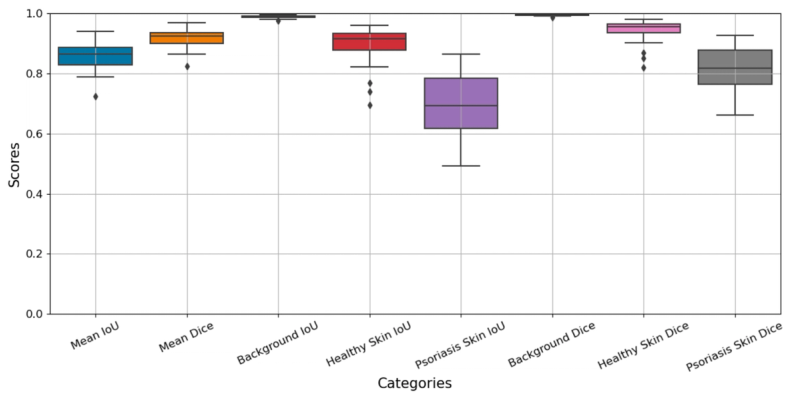

Before looking at BSA numbers, it is worth examining how well the AI system performed at the pixel-level classification task that underlies everything else. Two standard metrics were used: Intersection over Union (IoU), which measures overlap between predicted and actual regions, and the Dice coefficient, which measures spatial concordance.

Across all 35 images and three tissue classes, the system achieved a mean IoU of 0.858 and a mean Dice coefficient of 0.917. But the aggregate numbers mask an interesting pattern in the class-specific breakdown:

- Background: IoU 0.989, Dice 0.995. Near-perfect, as expected. Distinguishing background from body is a straightforward task.

- Healthy skin: IoU 0.895, Dice 0.943. Strong performance on identifying unaffected skin.

- Psoriatic lesions: IoU 0.689, Dice 0.812. Good, but noticeably lower than the other two classes.

The drop-off for psoriasis segmentation is not surprising. Lesion boundaries in psoriasis are often gradual rather than sharp; erythema fades at the margins, scaling varies in density, and the transition from affected to unaffected skin can be ambiguous even to expert observers. Overall, the model performs well, considering this involves the most difficult cases.

BSA Assessment: The Central Results

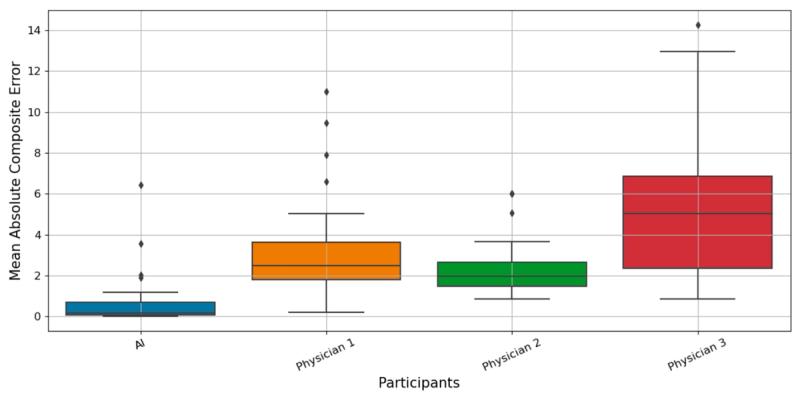

The headline numbers tell a clear story. When AI and dermatologist BSA estimates were compared against the consensus ground truth:

Mean Absolute Error (MAE):

- AI system: 0.668

- Dermatologist 1: 3.152

- Dermatologist 2: 2.310

- Dermatologist 3: 5.549

The AI's error was roughly one-third of the best-performing dermatologist's and one-eighth of the worst-performing one's. These are not small differences.

95% Confidence Intervals:

- AI: [0.463, 0.872]

- Dermatologist 1: [1.841, 4.463]

- Dermatologist 2: [1.165, 3.455]

- Dermatologist 3: [3.328, 7.770]

The AI's confidence interval is strikingly narrow compared to the dermatologists'. This reflects not just lower error on average, but much greater consistency. The AI performed at a similar level across different images, while the dermatologists' performance fluctuated considerably.

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE):

- AI: 1.514

- Dermatologist 1: 4.979

- Dermatologist 2: 3.164

- Dermatologist 3: 7.891

RMSE penalizes large errors more heavily than MAE, so the fact that the pattern persists under this metric confirms that the AI's advantage is not driven by a few easy cases; it holds even when the analysis is weighted toward the harder ones.

Correlation with ground truth:

- Pearson: 0.959

- Spearman: 0.969

Both near-perfect, indicating the AI's estimates tracked the ground truth with minimal systematic deviation.

Statistical Validation

A Kruskal-Wallis H test confirmed that error distributions differed significantly across the four assessors (AI plus three dermatologists). Pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction showed the AI system's errors were significantly lower than each individual dermatologist's (p < 0.001 in all three comparisons). This rules out the possibility that the observed differences were due to chance.

Evolution from the 2022 Study

Comparing the two studies side by side illustrates how the research program matured:

The 2022 study used 130 single images, one dermatologist comparator, a simple CNN, and a single-rater ground truth. It found ANN mean percentage error of 8.95% versus 27.84% for the physician. The AI PASS study used 35 full-body images processed through the complete SPREAD pipeline, three dermatologist comparators, a consensus ground truth from multiple experts, and anatomical segment-based analysis. It found AI MAE of 0.668 versus dermatologist MAEs of 2.31 to 5.55.

The sample size went down, but the methodological quality went up considerably. And the conclusion was the same: the AI system was substantially more accurate and consistent than human experts.

Why AI Outperforms at This Task

BSA estimation is, at bottom, a geometric measurement problem. You need to determine what fraction of the skin surface is covered by disease. Unlike severity grading, where reasonable physicians can disagree about whether erythema is a 2 or a 3, BSA is in principle an objective, continuous quantity. It should be measurable.

But in practice, clinicians estimate BSA poorly. The palm method introduces systematic error (the palm is not actually 1% of BSA). Mental integration of disease extent across the entire body is cognitively demanding and error-prone. Clinicians are susceptible to anchoring bias, perceptual illusions, and simple fatigue. The same dermatologist assessing the same photograph twice may produce different numbers.

The AI system avoids all of these problems. It evaluates every pixel independently, against learned criteria that do not drift with fatigue or mood. The same image always produces the same result, with zero intra-rater variability. The narrow confidence intervals in the AI PASS results are a direct consequence of this deterministic consistency.

This does not mean AI is "smarter" than dermatologists. It means that for this particular type of task, quantitative measurement of visible area, a pixel-by-pixel computational approach is inherently better suited than human visual estimation.

Limitations

Several important caveats apply. The cohort represented limited Fitzpatrick skin type diversity, and performance on darker skin tones remains to be validated. The consensus ground truth, while an improvement over single-rater annotation, still reflects the variability of human expert judgment. Thirty-five images is a modest sample, and multi-center validation on larger, independent datasets would strengthen confidence in the results.

Some anatomical regions remain genuinely difficult for photographic assessment, including the scalp (hair occlusion), skin folds (limited visibility), and areas typically covered by clothing. These challenges affect both human and AI assessors, but they may be more consequential for the AI, which cannot supplement visual information with tactile examination or clinical history the way a dermatologist can.

The severity classification component was not evaluated in this study. How well the SWIN Transformer grades erythema, induration, and desquamation is a separate question that awaits its own validation.

Looking Forward

The AI PASS results point toward several practical next steps. Validation on larger, more diverse populations is the most pressing priority. Multi-center studies would address questions of generalizability. Prospective integration into clinical workflows, presenting AI-generated BSA estimates alongside clinician assessments in real time, would test whether the technology actually changes clinical decisions and improves outcomes.

The methodological approach generalizes beyond psoriasis. Vitiligo (VASI), eczema (EASI), and atopic dermatitis (SCORAD) all involve regional assessment of skin disease extent, the same type of quantitative measurement task at which the AI system excels. Adapting the SPREAD Framework to these conditions requires changing the disease-specific segmentation model, not rebuilding the architecture.

Conclusion

The AI PASS study provides clear evidence that AI-based full-body dermatological analysis outperforms human dermatologists in psoriasis BSA estimation, not marginally, but substantially. The AI achieved an MAE of 0.668 versus dermatologist MAEs of 2.31 to 5.55, with narrower confidence intervals and near-perfect correlation with ground truth. The statistical evidence is robust (p < 0.001 across all comparisons).

The right interpretation of these results is not that AI should replace dermatologists. It is that BSA estimation, a quantitative measurement task that humans perform inconsistently, is well suited to computational automation. Integrating AI-assisted measurement into clinical practice could reduce inter-rater variability, improve the reliability of severity indices, and provide clinicians with a consistent, objective baseline to complement their clinical judgment.

The broader trajectory is encouraging. From the initial proof-of-concept validation to the SPREAD Framework to the AI PASS comparative study, each step has strengthened both the technical capabilities and the evidentiary base for AI in dermatological assessment. The next steps (wider validation, clinical integration, and extension to other conditions) will determine whether these research findings translate into routine clinical practice.

References

Breslavets, M., Sviatenko, T., Breslavets, D., Hrechkina, N., Motashko, T., Lapa, T., Borodina, G., & Breslavets, A. (2024). AI versus dermatologist performance in psoriasis body surface area assessment: A ground truth-validated, anatomical segment-based comparative study (AI PASS). Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 38(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.20456

Breslavets, M., Sviatenko, T., Breslavets, D., Hrechkina, N., Motashko, T., Lapa, T., Borodina, G., & Breslavets, A. (2024). AI versus dermatologist performance in psoriasis body surface area assessment: A ground truth-validated, anatomical segment-based comparative study (AI PASS). Paper presented at the EADV Symposium, St. Julian's, Malta.

Breslavets, M., Shear, N. H., Lapa, T., Breslavets, D., & Breslavets, A. (2022). Validation of AI application in clinical dermatology. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 86(1), 201–203.

Was this article helpful?

Your feedback helps us improve our content

Related Articles

Read more news

Stay up to date with our latest announcements