The SPREAD Framework: A Novel AI Architecture for Comprehensive Dermatological Assessment

The SPREAD Framework processes full-body clinical photographs through a multi-stage pipeline, segmenting anatomical regions and computing standardized dermatological metrics like BSA and PASI.

Introduction

This article describes peer-reviewed academic research that preceded and informs the development of Dermi Atlas. The algorithms and methods discussed are not currently available as features in any Dermi product. Dermi Atlas is a clinical photography and image management platform. The integration of research capabilities into the platform is a long-term development goal.

The initial validation study published in JAAD in 2022 showed that a convolutional neural network could outperform a dermatologist at estimating psoriasis BSA from individual photographs. That was a compelling result, but also a limited one. Clinical practice does not typically involve analyzing single cropped images in isolation. A dermatologist assessing a psoriasis patient looks at the entire body, mentally summing disease extent across regions, factoring in which body parts are affected, and integrating all of that into severity indices like PASI or BSA. Replicating that kind of holistic assessment requires something considerably more sophisticated than a single image classifier.

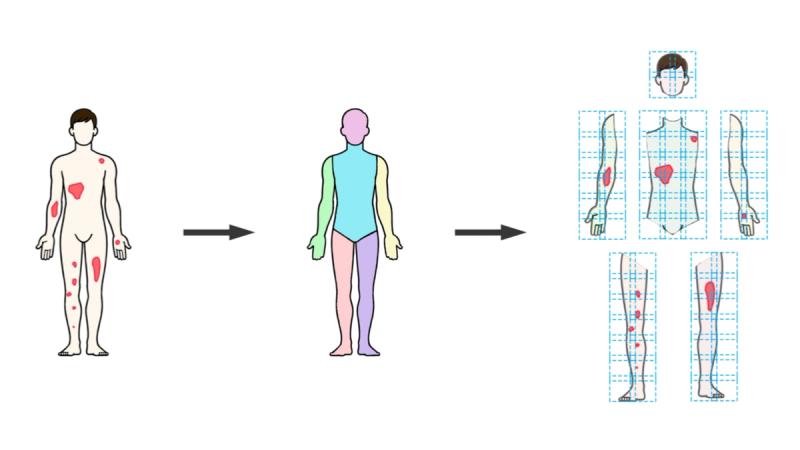

This is what motivated the development of the Skin Patch-based Regional Extent Assessment for Dermatoses, or the SPREAD Framework. Rather than treating each photograph as an independent estimation problem, SPREAD processes full-body clinical photographs through a multi-stage pipeline that segments the body into anatomical regions, analyzes each region at high resolution, and aggregates the results into standardized dermatological metrics.

The design goals were practical as much as technical: the system needed to standardize metrics like BSA, PASI, and VASI; run on consumer-grade hardware rather than requiring specialized medical imaging equipment; assess both whole-body and regional disease extent; preserve the morphological fidelity of skin lesions throughout processing; and generalize across different dermatological conditions.

Architecture at a Glance

The SPREAD pipeline has five stages, each feeding into the next:

- Body Segmentation: DensePose identifies anatomical regions in full-body photos

- Patch Formation: A sliding window protocol divides each region into uniform, overlapping tiles

- Spread Analysis: A UNet 3+ model classifies each pixel as background, healthy skin, or affected skin

- Severity Analysis: A SWIN Transformer grades lesion characteristics (excluded from the current study)

- Metric Aggregation: Regional predictions are combined into whole-body BSA, PASI, and related indices

The modular design is deliberate. Each component can be improved or swapped independently. If a better body segmentation model comes along, it can replace DensePose without rebuilding the entire pipeline. This also means the framework is not locked to psoriasis; replacing the disease-specific segmentation model adapts it to vitiligo, eczema, or other conditions.

Stage 1: Body Segmentation with DensePose

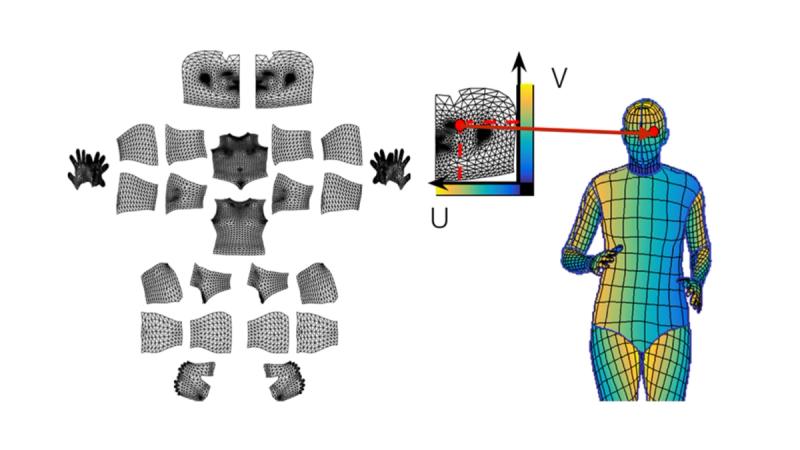

Everything starts with figuring out where the body is in the photograph and what part is what. The SPREAD Framework uses a custom implementation of Meta's DensePose, which maps 2D image pixels onto a 3D body surface model. In practical terms, DensePose looks at a full-body photograph and produces a detailed segmentation mask labeling each pixel by anatomical region: head, anterior torso, posterior torso, left upper arm, right lower leg, and so on, totaling thirteen regions, assessed bilaterally.

This is more than simple body detection. DensePose establishes spatial correspondence between the image and a standardized body model, which means the system knows not just that a pixel belongs to the torso, but roughly where on the torso it falls. The spatial positioning data is preserved for later use when reassembling predictions.

One useful property of DensePose is that it can estimate body contours even where clothing or other occlusions hide the skin. This matters because the downstream segmentation models are trained to recognize and disregard non-skin areas. DensePose defines the body boundary; the later models figure out what is skin, what is clothing, and what is disease.

Cleaning Up: Connected Component Analysis

DensePose segmentation is not perfect. The output sometimes contains stray pixels, small clusters incorrectly assigned to an anatomical region, scattered around the image like noise. Left uncorrected, these would introduce errors into the downstream analysis.

The fix is a post-processing step based on Connected Component Analysis (CCA). For each anatomical region label in the DensePose output, the system identifies all contiguous pixel clusters sharing that label, retains the largest one (which is the actual body part), and discards the smaller fragments. The implementation uses OpenCV's connectedComponentsWithStats on 8-connected binary masks. It also computes the bounding box around each retained cluster, which is needed for the next stage.

This is a simple but effective filtering step, grounded in the observation that real anatomical regions form large, spatially coherent clusters while artifacts are small and scattered.

Stage 2: The Sliding Window, Patch-Based Preprocessing

After body segmentation, the framework needs to feed each anatomical region into a neural network for disease classification. The catch is that these regions vary wildly in shape and size. An arm segment is long and narrow. The torso is roughly square. Different patients produce different absolute pixel dimensions.

The obvious approach, resizing everything to a fixed square, is actually a bad idea for dermatology. Stretching or compressing an image distorts the morphology of skin lesions. A plaque that is round on the patient would appear elliptical after non-uniform resizing, and the network would learn from distorted representations of disease. This might sound like a minor detail, but morphological fidelity directly affects classification accuracy.

SPREAD handles this with a custom sliding window protocol. Instead of reshaping images to fit the network, it tiles each anatomical region into a grid of overlapping patches that the network can process at its native resolution. The process works as follows:

First, the algorithm calculates the dimensions of a Patch Grid Matrix (PGM) based on four parameters: Patch Size (P, typically 384 pixels), Overlap Value (O, ranging from 0 to 0.5), Zoom Coefficient (Z, from 0.05 to 1.0), and the Input Dimension Size (D). The original image is rescaled according to the Zoom Coefficient and centered on the PGM. The PGM is then subdivided into uniform P×P tiles with the specified overlap between adjacent tiles.

The overlap is important: it ensures that lesions near patch boundaries are seen in full context by at least one patch, avoiding edge artifacts in the classification. Higher overlap values provide more redundancy but increase computation time.

Stage 3: Semantic Segmentation with UNet 3+

The classification engine at the core of SPREAD is a UNet 3+ model, an encoder-decoder architecture designed for medical image segmentation. UNet 3+ builds on the original U-Net concept by adding full-scale skip connections that fuse features at multiple resolutions. In practice, this means the model can attend to both fine local details (the edge of a psoriasis plaque) and broader context (whether that edge is surrounded by erythema or normal skin).

The implementation uses either VGG16 or ResNet101V2 as a frozen backbone, leveraging features these networks learned on large natural image datasets via transfer learning. Each 384×384 patch goes in, and out comes a probability map assigning every pixel to one of three classes: background, healthy skin, or affected skin.

Skin Extraction

A separate auxiliary model, an FCN8 network with a VGG16 backbone, handles a simpler but important preprocessing task: distinguishing visible skin from clothing, shadows, and other non-skin elements. This runs before the disease segmentation model and masks out regions where classification would be meaningless. Because the task is relatively straightforward (broad boundaries, no fine pathological features), this model operates with lower overlap (0.2) and a coarser zoom factor (0.5), keeping its computational cost modest.

Recombining Overlapping Predictions

After running inference on all patches within an anatomical region, the system needs to stitch the predictions back together into a single coherent mask. Where patches overlap, pixels receive multiple independent predictions.

The recombination uses a union-based approach: an aggregate matrix accumulates all patch predictions, and for overlapping regions, pixels classified as positive (affected skin) in any contributing patch are treated as positive in the final mask. The unified masks are then layered hierarchically (background first, then healthy skin, then affected skin) to ensure mutual exclusivity. Finally, the aggregate mask is cropped to remove padding and rescaled to match the original image dimensions.

Stage 4: Severity Classification (Future Work)

The SPREAD Framework also includes a severity classification component built on the SWIN Transformer architecture. For each patch, the model grades erythema, induration, and desquamation on the standard 0–4 ordinal scale used in PASI scoring. Individual patch scores are aggregated via global average pooling to produce region-level severity estimates.

There is an open methodological question here: average pooling gives a representative severity score across the region, but global max pooling, reflecting the highest severity visible in any patch, might be more clinically meaningful for identifying patients with severe localized disease. This remains under investigation.

The severity component was intentionally excluded from the AI PASS comparative study to keep the evaluation focused on spread quantification. Performance on severity grading is a separate validation question.

Training and Data Preparation

The framework incorporates three distinct model types, each trained on dedicated datasets: psoriasis lesion segmentation, severity classification, and skin extraction. Training images were compiled from dermatology clinics and publicly available repositories, with all semantic segmentation annotations (pixel-level masks identifying background, healthy skin, and psoriatic lesions) validated by dermatologists.

An important methodological detail: the 85/15 training-validation split was applied before patch creation. This prevents patches from the same original image from appearing in both sets, a form of data leakage that would inflate apparent generalization performance. Training used multiple patch configurations (1×1, 1×2, 2×1, 2×3, 3×2) to expose models to features at different scales, supplemented by positional and rotational augmentation. Performance was tracked via IoU, Precision, Recall, and Dice Coefficient.

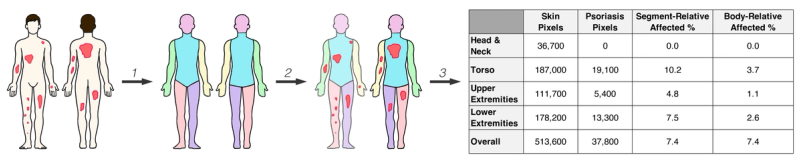

Putting It Together: PASI Automation

To demonstrate the framework in action, Breslavets et al. applied SPREAD to fully automate PASI calculation. For each patient, the system creates an instance subdivided into anterior and posterior body projections, further segmented into thirteen anatomical regions. Each region stores pixel counts for affected and healthy skin, segment-relative affected percentage, and body-relative affected percentage.

This hierarchical structure supports not just whole-body BSA but also regional analysis and, when combined with severity data, full PASI computation. The architecture generalizes naturally to other conditions: replace "psoriasis lesion" with "depigmented region" and the same pipeline computes VASI for vitiligo.

What Makes This Different

Previous AI tools in dermatology typically operated on single images in isolation. SPREAD is different in several ways that matter clinically. It processes full-body, multi-view image sets rather than individual photographs. Its modular architecture means each component can be refined independently. The patch-based approach preserves morphological fidelity without sacrificing computational efficiency. And the framework's design is condition-agnostic at the architectural level; swapping in a different disease model adapts it to a new clinical domain.

The next article in this series presents the comparative results from the AI PASS study, showing how this technical architecture translates into measurable clinical performance gains relative to dermatologist assessments.

References

Breslavets, M., Sviatenko, T., Breslavets, D., Hrechkina, N., Motashko, T., Lapa, T., Borodina, G., & Breslavets, A. (2024). AI versus dermatologist performance in psoriasis body surface area assessment: A ground truth-validated, anatomical segment-based comparative study (AI PASS). Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.20456

Breslavets, M., Sviatenko, T., Breslavets, D., Hrechkina, N., Motashko, T., Lapa, T., Borodina, G., & Breslavets, A. (2024). AI versus dermatologist performance in psoriasis body surface area assessment (AI PASS). EADV Symposium, Malta.

Breslavets, M., Shear, N. H., Lapa, T., Breslavets, D., & Breslavets, A. (2022). Validation of AI application in clinical dermatology. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 86(1), 201–203.

Gong, H., Cao, L., & Cai, Y. (2021). UNet 3+: A full-scale connected UNet for medical image segmentation. ICASSP 2021 - IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing.

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2015). Deep residual learning for image recognition. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR).

Liu, Z., Lin, Y., Cao, Y., Hu, H., Wei, Y., Zhang, Z., Lin, S., & Guo, B. (2021). Swin Transformer: Hierarchical vision Transformer using shifted windows. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV).

Simonyan, K., & Zisserman, A. (2015). Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

Was this article helpful?

Your feedback helps us improve our content

Related Articles

Read more news

Stay up to date with our latest announcements